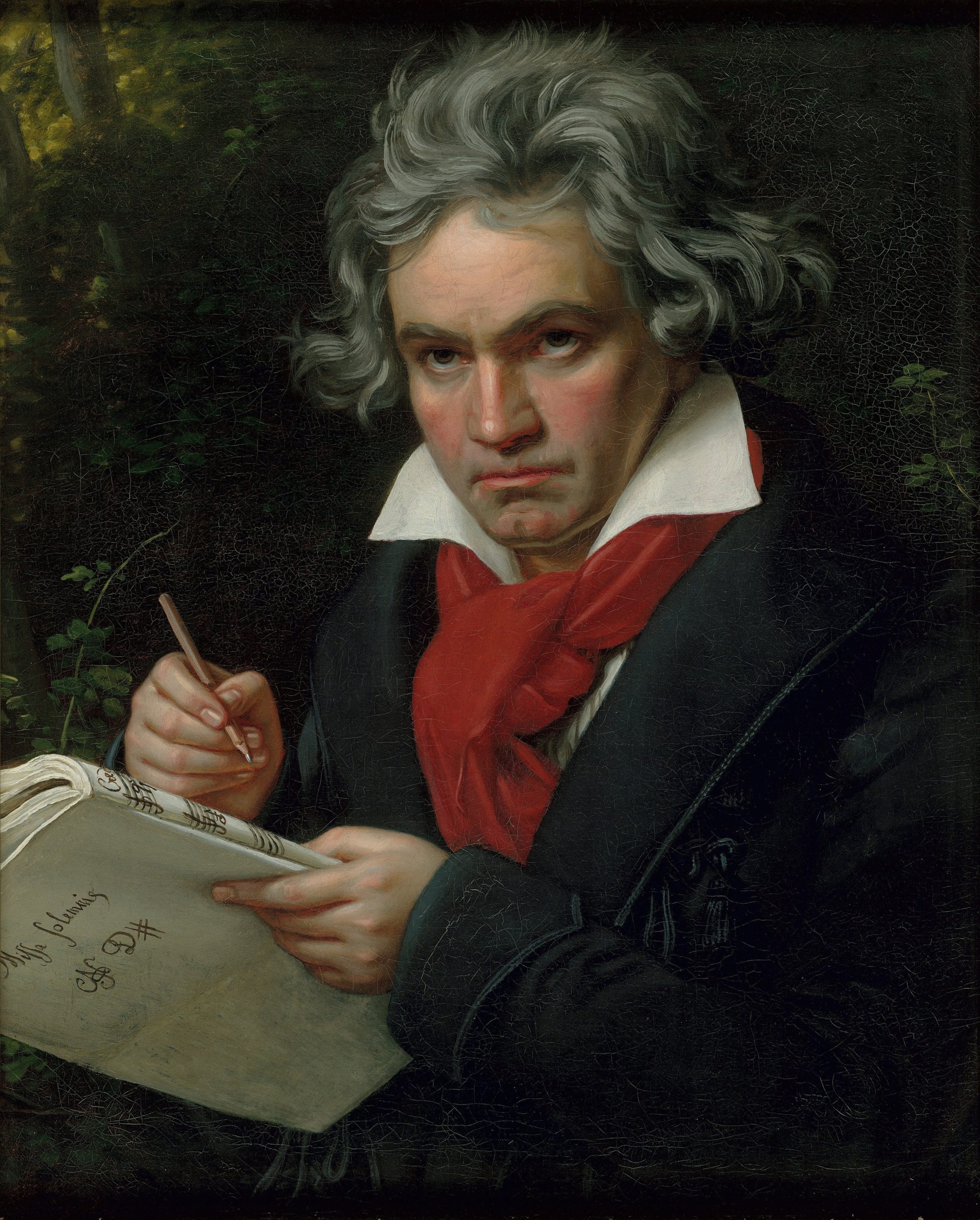

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) is an unreplaceable milestone in the history of Western civilization, whose dimension is so crystal clear that, no matter the weaving moment of political and moral fashion of the day, his music is executed everywhere in the world. The reason is simple. Those who had the fortune to encounter and understand his music will never stop to be baffled by it, by its unique capacity to embed human sentiments inside a strict iron rational logic.

Differently from Chopin, who is so emotional to be undigestible to some, differently from Bach, whose love for abstract structure makes him the embodiment of the XVII century mechanicism, Beethoven is the unique pinnacle of intellect, reason and sensibility, a rare Kantian union of different aspects of human cognition and experience. But what about the life behind the music? Is Beethoven a man unlike many others? The answer is ambivalent when reading a selection of biographical notes and other annotations left in his Conversation Books and here, I will only draw some remarks without entering in the specificities of Beethoven’s life, which is assumed sufficiently known to the reader.

What I want to report here are the common threads that Beethoven shared with many other great thinkers. Yes, thinkers, because Beethoven only by accident was a musician, as his music is a philosophical act as Kubrick’s movies. As argued elsewhere, philosophy is not the land of written language necessarily but of argumentation for the sake of truth reached through a merciless critique of language. As such, it is pointless to draw a rigid line between Beethoven and Kant or Spinoza, to mention two major thinkers whose life wasn’t as different from Beethoven’s – Gens una sumus.

Personal Research and Autodidactic Studies – First Sign of the Worst Intellectual Sins

First, although Beethoven studied under major musicians and experts, Haydn being the most relevant, he grew up under the direction of his father, who literally forced him to be the ‘next Mozart’, a freak able to be economically profitable in exhibitions around the courts of Europe. The tragic dependency of artists and thinkers on external whimsical authorities will never leave them fully free to pursue their arts until the XX century when, indeed, the quality and appeal of music start to fall beyond any hear able to listen. Unpressured by the economic market and released from the confrontation with more successful ways of expressions, the now subsidized thinkers retreated even further in the abstract realms of the nonsensical speculative research without any imaginable scope and purpose. Needless to say, Beethoven did not have this luxury at all. With all the cries of contemporary researchers and aspiring PhDs, they are on average far more in the position to produce any garbage they like in comparison to what Beethoven had to do to live his economically miserable life. (Of course, the author of the post is the first in the list in producing meaningless unprintable jots!)

Beethoven was psychologically and physically forced to study music in many forms and ways even before five and, since then, he developed a ‘dangerous’ personal sense of what he wanted to achieve being the sinner of autonomous self-didactic learning. No masters behind him, only himself. In fact, he was not successful as Mozart (but already buried in a common grave around 1791) and he is the typical example of a non-naturally born genius, whose greatness is taken away from the marble through painful daily chisel’s work. Not because Mozart was the exemplary case of a lazy talented individual able to write music as other people breathe, but it makes the point.

Beethoven kept studying more in isolation than with mentors, at least in the Kantian sense of autonomy. Indeed, Beethoven never fully liked Haydn as a teacher, though he stated that he was among the greatest musicians (but clearly less so than Mozart and Bach). As a result, Beethoven started to leave the neo-Haydnian style quite early on (let’s think about the significant difference between the Symphony 2 and Symphony 3). And since then, he was exploring the purely Beethoven’s space, whose uniqueness is indeed to be the only musician so able to combine all aspects of human existence with full appreciation for the rational side of inner component of human experience (nothing can show the extreme of Beethoven’s production than the progression of his piano production from the first Piano Sonata to the Variations on a Theme of Diabelli).

Surprise, Surprise – A Relentless Hard Worker neither a Misanthropist nor Misogynist

As all great human minds before and after him, Beethoven worked incredibly hard, that is, he was relentlessly pursuing his intellectual vision with no rest, epistemologically speaking – that is, in the abstract understanding of his idealized endeavor. Indeed, Beethoven’s mind can only be stopped by the frail limitations of his very concrete human body which, indeed, were many. And when the body didn’t betray him, the brain fatigue can come to the rescue saving Beethoven from being even more productive as he could have been.

He suffered from all sorts of major and minor diseases, the most famous of which is his deafness, far from being the only physical obstacle to Beethoven’s efforts to have a ‘normal life’. Firstly, like Kant, he was neither a misanthropist nor misogynist and, like Kant, he was in love from time to time to women inaccessible for a priori political or economic reasons. For what is known, Kant contemplated marriage a couple of times and he speculated about it (as, after all, he was a philosopher) with friends (who never fail to push the single to do his due to the future of society – as they cannot socialistically ‘give back’ much wealth, at least they can produce future bodies).

However, unlike Kant, Beethoven surrendered to the status quo fighting much more fiercely and in so doing spectacularly losing many more battles. There are some pathetic letters in which Beethoven clearly tries to reach the hearts of (not very much) potential lovers. He was very successful in being very unsuccessful – far from being a uniqueness of Beethoven, this trait is shared across many other successful losers like Friederich Nietzsche, to name one. However, differently from Nietzsche, Beethoven never lost his mind though both likely had some ‘free encounters’ with the oldest of the professionals. This should not sound like a critique but only the fact that both of them suffered sexual loneliness to a high degree and they both paid for it (at least metaphorically, as the bills were not saved anywhere, pity as we could have calculated the inflation rate between Beethoven’s and Nietzsche’s times with some degrees of precision). In one note, the great musician clearly asks for help from a friend in ‘finding a wife’. Alas, that wasn’t anymore the XVII century and that way of finding the solution to the problem was unavailable, at least to him. It worked for Kepler, who was then in search of quietness and loneliness after his wife and kids brought even too much joy (and noise) to his otherwise quite existence.

Beethoven, like Kant, appreciated ‘social life’ at least in the first part of his existence. But his deafness sealed an existence of inner life or forced isolation. He was very ashamed of having developed this disease and the process of psychological acceptance took quite some time; years, indeed. He felt ashamed and isolated at the same time, forcing him to refuse closer personal contacts. Tragically and ironically, this happened approximately when he started to have some public recognition, and he could have found ways to solve his need for a partner if only the abhorrent disease would have left him in peace. But life does not leave to the limited humans the decision to when something has to happen and, once again, Beethoven’s wellbeing was hampered forever from isolation, lack of a partner, and the desperate need for human kindness.

Chasing the Money very Unsuccessfully – But What a Glory!

Talking about fame and recognition, Beethoven was always and to the end obsessed by economic insecurity and lack of stable stream of funding. He complains consistently about being very close to insolvency, especially when he had to fight for his loved and tortured nephew, Karl – another major tragedy of Beethoven’s existence. Money was always a relentless reminder of him never being in a position of stability and wealth. He had literally to chase the money everywhere he could, especially from whimsical aristocratic patrons who did not always support him or, sometimes, they simply died before paying. If the state research funds seem to be unpredictable enough, nothing in comparison to an old European aristocrat entitled with acquired titles by birth.

In fact, Beethoven, like an average contemporary Italian, was chasing a permanent low-income but stable job. Ideally, he would have liked to be court’s musician or something in that line whatever the nomenclature of the day. Not a glorious very well-paid job indeed for one of the greatest composers of the richest and most prosperous civilization! Kant, in this regard, was much luckier than Beethoven, as he was a teacher, a dreaded ‘sophist’ in Plato’s neo-idealist parlance that always favor politics and power to trade and money only because politics can force the money into his pockets without him producing it. Coherently, Plato preferred to travel everywhere to gain political support so, I assume, he picked up the right way to chase support, risking his life and head at least in a couple of recorded circumstances.

Kant’s existence was based on the fees that the students paid directly to him for his lecture before he finally got a more stable position. Instead, Spinoza, whose Jewish origin possibly opened him up to the love for physical work, made a living out of polishing lenses – before the volatile glass powder destroyed his lungs far more efficiently than many pockets of cigarettes (at the time fortunately unavailable as otherwise he wouldn’t have even finished his Ethics dying even younger). In spite of being very well connected with courts and always part of ‘royal projects’, Leibniz was always chasing the money only to discover that he always needed much more. Leibniz’s principle of logic identity is well understood: money is never enough. Slightly better than those mentioned and the ugliest of all, Hegel was the married head of a secondary school before being enrolled as a glorious professor and dying of cholera, an appropriate way to end a brilliant career. Of course, all readers can agree that these examples not only are not unique among great minds, but they tragically show the discrepancy from the greatness of the ideas and the sheer reality of human success.

In this regard, however, all these thinkers are united by the general recognition that rational existence does not take much and that life without reason is unworthy. As Spinoza more clearly and wearily recognized, a rational human being asks much less than a whimsical, uneducated and unruled individual to exist. After all, to be a great musician in theoretical terms, all it requires is discipline, time, effort and paper and ink. Paper and ink aside and all things considered, as scarce as those resources are in the ordinary human population, those are almost given for free to those who can produce the ideas requested to translate them into pure forms of art (no matter the discipline). In fact, from Kant to Beethoven, they all appreciate that they don’t like living for chasing a payment but for a greater cause, the cause of human intellectual progress instantiated by their own way to express it or, in my own understanding, they embrace what it takes to formulate the eternal truths. They worked a lot to not work at all, so to speak, so much they abhorred ordinary life as usually conceived.

Peer Pressure, Complaints about Other People and Envies

The life of scientists is about breaking the novelty for first. Far from being a purely speculative, inertial endeavor, science is a quite exciting space to be. Scientists (philosophers, artists…) all want to enjoy the public recognition ahead of their peers. This was perfectly showed by the life of Christiaan Huygens, who simply was overstressed by the ‘inflamed exchanges’ of those who accused him of unfair exploitation of others’ ideas (invariably wrong accusation and, exactly for that reason, much more painful). Unlike very similar cases like Descartes, Newton and Leibniz who never refused a ‘spiced fight for ideas’ (especially theirs), Huygens was a simple soul, who wanted only to study peacefully. Unfortunately, even for very peace-loving individuals like him, the more emotional and stubborn less-kind more-human scientists disagreed with him in his quest for ‘just science’. Peers are there, always looming to find weaker spots in other peers’ existence and research, a typical feature of human social dynamics no matter the time and age.

Tragically, indeed, thinkers of all sorts have to accept the peer’s presence as they need to be supported by external validation, aggregate dispersed evidence and opposing facts, to know what other alternative ideas can challenge their own point of view rightly or wrongly. As a result, there is a continuous paradoxical tension between those who are, in that moment, allies and opponents at the same time. Of course, Beethoven was no exception. Indeed, after health, wealth and loneliness, Beethoven relentlessly complains about other people exploiting his weaknesses, such as his lack of talent for ‘trade’ (and so finding money), his incapacity to get the favor of the press (so unheard!) or rumors that discredited him in front of valuable or valued third parties. There is no reason to believe that he was a very good judge of everybody around him as, in the majority of the cases, human superficiality, incompetence, and simple lack of care can explain almost invariably all the acts that on average can be attributed to some form of conspiracy (right, Beethoven – the conspiracy theorist!) It is not very important to establish what Beethoven rightly believed as he almost invariably forgets to give any evidence to support his claims.

The fact is that the perception that Beethoven developed about his peers and general community remains. Those potential misperceptions are invariably the same that are indicated by everybody who spends sufficient amount of time in any profession mainly related to intellectual achievements. Indeed, if fame and public recognition are the main intersubjective tangible value to be ascribed and tested by the peers and general community, it is quite hard to understand why this all-fame thing does not come so naturally after so many great pieces of work! And as Nietzsche would have pointed out, we can live in pain, but we need a reason. And nothing as the human mind is able to find wonderful explanations for the alleged failure. Being the devil or the absence of it, being the ignorant population or the envious peers, no matter the cause, a cause must be found for the lack of human appreciation.

Stress, Speculations and Overthinking – Isolation and Speculation

In an age of social media, the only thing that matters is to rediscover the obvious every single day as if it was a wonder of the last minute. Humanity is so self-isolated within the tiny constraints of the ordinary imagination that on average even the sun is a major discovery on a daily base – in spite of the fact, of course, everybody knows that under the sun there is never something new, but the sun itself – that stupid star – that is ever changing. Of all the wonderful novelty of the present is the appreciation for stress, the major alleged cause for all possible problems. Beethoven was an expert on the subject matter.

As already stated, Beethoven was vexed by his general lack of economic income, mainly based on his sheer productivity, that is, by selling his artworks. It would be an interesting proposition worth of a mind like Ludwig von Mises to understand what a price can be attached to the Symphony 9 as von Mises himself considered it priceless. Of course, the solid social security of the time was very succinct, to say it mildly. As a result, the good composer had to keep composing almost in any circumstance making his life continuously exciting. Secondly, thanks to his deafness, he was forced into a self-inflicted social isolation that almost led him to suicide (it is unclear where and when, but it is highly likely that it must have happened and, if not, the logical possibility fully explored). Thirdly, as seen, an infinite series of major and minor health issues forced him to live under continuous uncertainty. In this sense, the most stressed people of the present who can enjoy a level of food security that Beethoven could have only envied (sometimes he had to write friends to send him food as bad as it was), they would appreciate how better off they are comparing the doctors and their prescriptions to those available in the good old days. Indeed, the physicians at the time suggested baths, powders and ‘change of air’ with quite some liberty to the point that the cure was almost invariably worse than the disease. For example, Beethoven explicitly complains that the baths did not help his hearing and, if anything, it deteriorated (one wonders why). This was a great time to live, evidently as any drug and medicine or prescription can be as fatal as the starting disease.

As Beethoven realized that economic hardship, physically unstable health and mental exhaustion were insufficient to make his life exciting and fulfilling enough, he realized that he needed to add another adventure to the list of his misfortunes. He felt the need to have a judiciary battle to be sure to be worse off even in front of the law. Hence, he fought hard to have his nephew, Karl, under his tutelage. Apparently, the court of justice believed that Beethoven was right in believing that Karl’s mother was not an appropriate example and tutor for the son. At the same time, given the age and perception, it is hard to tell if it was better to be under an imperfect mother or a tyrannical and quite impossible uncle. As Karl tried to suicide stating Beethoven’s harassment as cause, we can rest reassured that we have a convincing verdict on the point.

Related to the previous point and for those who love to rediscover the obvious, people who live by the mind also die by the mind. Meaning, they continuously suffer from psychological exhaustion, ‘burnout’ in contemporary jargon. We do know that Beethoven wasn’t able to work for days or even weeks and he had to walk, sometimes even leaving Vienna. The cycle of production and exhaustion was endless, as Beethoven many times had to make changes to his own products even when sent to publishers. Of course, almost all known thinkers suffered exhaustion from time to time – if they paid attention to record it. David Hume, famously, essentially needed to travel from the Scottish mountains to France to forget the fatigue of the (essentially ignored) Treatise on the Human Nature.

However, it is impossible not to mention another interesting feature of human existence that Beethoven lived to the full. As he was tied to letters to get in contact with people far from him, usually in Vienna, he was obsessed many times and overthinking about others’ reactions, feeling and perceptions. After all, at the time, the correspondence can take days even when in short distance. For example, if he wanted to know what a friend was doing in a close city, likely the letter could have taken one or two days. Meanwhile, his mind relentlessly was left in wonder on what the other person was actually thinking. A tragically ironic example is offered when he wrote to the husband of a woman who possibly misunderstood Beethoven’s intentions… One letter was written to her, one to the husband and finally a letter was written to both asking for quick reassurance about their own feelings and perceptions. The style clearly shows anxiety, fear and overthinking but, of course, as many overthinkers know, it is not always easy to understand when thinking is not overthinking, right? With perfect information or insight, the judgement call is not hard, but meanwhile it is hard to tell, especially when left alone in lonely despair.

The Greater Cause – I live Only in My Music

Reading the selection of autobiographical notes in a recent publication was sufficiently hard and painful experience. Not because there is nothing special about a human being ranting about his problems (and something could be said about the sadist who created the ranting compilation as, I am absolutely sure, there must have been much more interesting material), but exactly because there was almost nothing else left but a couple of observations about something important.

The reader should not be deceived by the irony in this text. Indeed, the author only knows too well that Beethoven’s life is special exactly because it is all but special. The only difference between the greatest composer and the rest of us is not about his miserable life, with all his travesties and imperfections, loneliness and overthinking, burnouts and insecurity. We all share it. The difference is that in front of all the opposite forces of the known and unknown universe, Beethoven was indeed able to write music that gives peace when there is no hope, gives joy when there is misery, energizes where there is despair. He transformed human existence into something we can hardly easily reconcile with what we do. And then the irony is on us the one who can only humbly admire an imperfect human being able to write for all humanity as if it was the most obvious thing to do. If nothing else, I will always be grateful to somebody who never met me and gave me the best of himself when I needed a friend and there was none. Beethoven was always with me reminding me that even in the face of the worst tragedy, it is possible to be beyond the misery of human existence.

Beethoven, like all the other great minds before and after him, with all his weaknesses and faultiness, only and consciously claimed to live for something beyond his blood and bones, beyond the chase of food, wealth, and people. For people like him, human life is everything that stands in between them and greatness, which is also part of human existence but in a different shape and form. Like so many others, Beethoven only knew that it was better one thing: to be feverishly and restlessly alive in the mind because, at least there, perfection through rationality can be found despite all the laws of thermodynamics.

Be First to Comment