(1) We were not supposed to be born like beasts.

Particularization on (1)

(2) I was not supposed to be born like a beast.

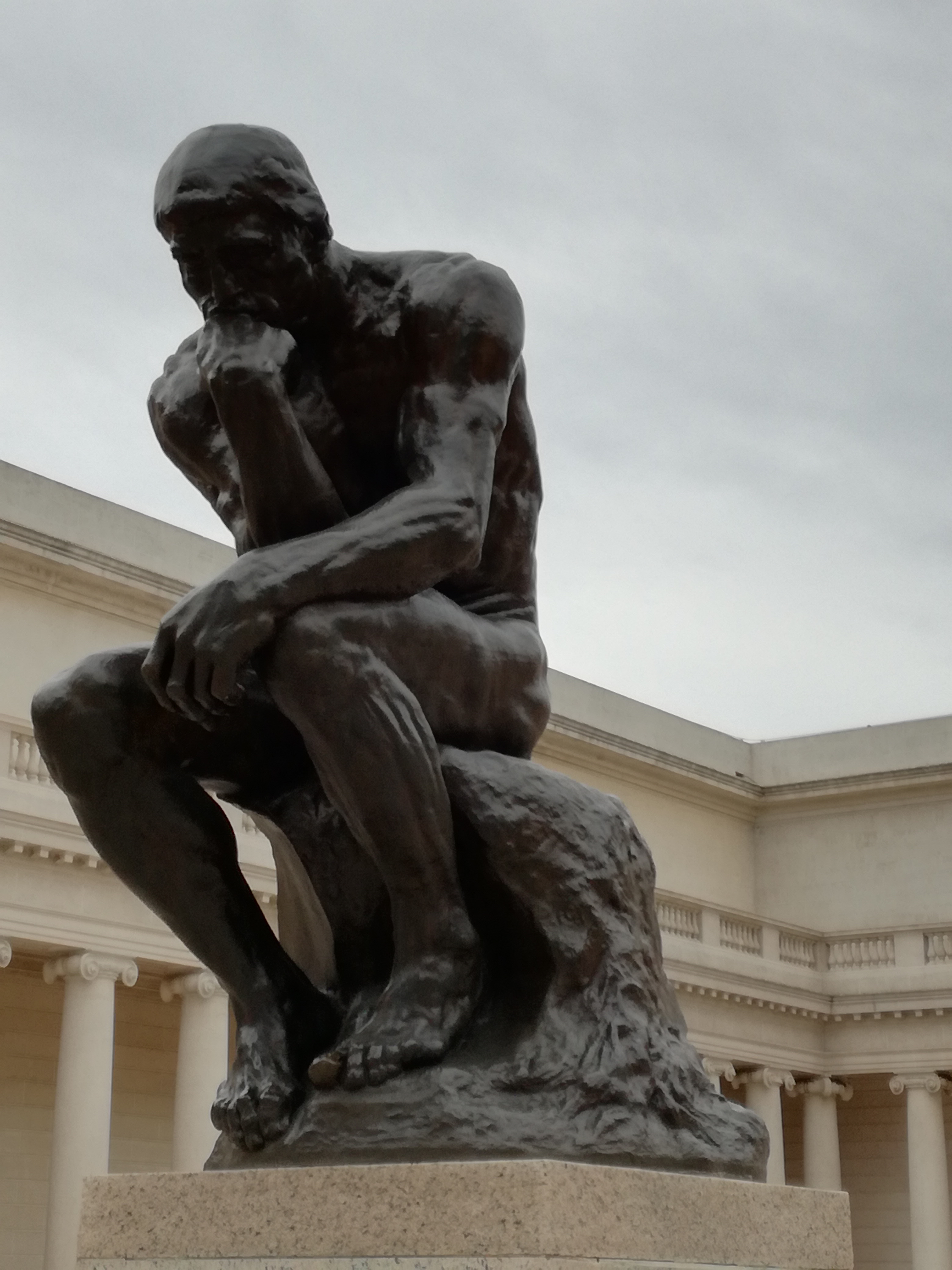

Dante + Logic + Me

Introduction – Rational Mysticism and Theory of Eternal Truth

Since I formulated the first conception of the theory of the free creation of eternal truths,[1] I immediately realized that I was opening the door to a peculiar form of mysticism. This was not an appreciated opening, to be fair. Any rationalist is, by very nature, against any principle that gives up the capacity of reason to formulate its principles and derive its theorems. However, the theory appeared to be compatible with a specific version of mysticism when it comes to how the truths are, in fact, generated.

Already the name of the theory seems to be against the tastes of analytic philosophy. Moreover, it has a specific universal afflatus, which is usually lost in the current philosophical production. To be more precise, it is left to the continental philosophers, who are well known to be as general as vague. Digging into a topic such as mysticism will bury the theory under all the tastes of current analytic philosophers, among which I still place myself – though I am open to any form of deep thinking. The eternal truth theory wants to be what philosophy used to be: a universal view of the world from nowhere, a vision, an inspiration, but also a consistent conception of the world. This is not welcomed anymore, and I, myself, see why. Philosophy exhausted these kinds of approaches between Greek and modern philosophy when the archetypical visions of the world were formulated. From that moment on, after Nietzsche, let’s say what can be done is to refine the portion of those visions better and better. It is a process of continuous refinement and improvement, not of invention, so to speak.