Per Edoardo Nesi, la vita non s’accontenta di scuotere, mentre ambisce a far sdraiare, per il “conto totale”. Forse sarà utile “l’allenarsi” all’attrazione per una…

...all we need is philosophy

Per Edoardo Nesi, la vita non s’accontenta di scuotere, mentre ambisce a far sdraiare, per il “conto totale”. Forse sarà utile “l’allenarsi” all’attrazione per una…

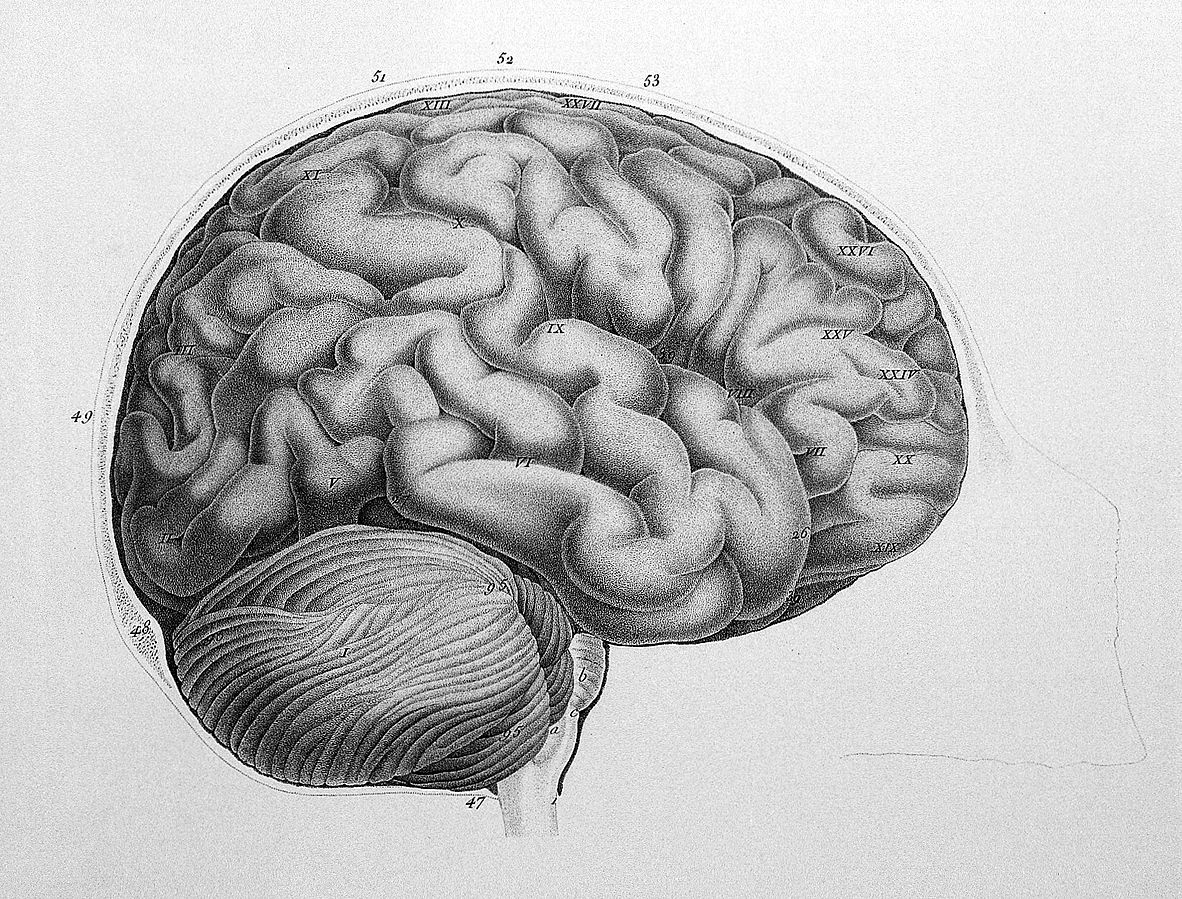

How do you define intelligence in the cognitive domain?

I never delved deeply into the intelligence-mind problem. Defining intelligence is a slipper problem and, in my opinion, not necessarily very interesting. Moreover, there is too much talk about it, which shows that we are possibly hitting a wall. When I first read Turing and approached the philosophy of mind, I never believed there was much promise in that space (definition of intelligence) for many reasons. One reason is the significant confusion about what we can confidently claim to know versus what remains unknown or not fully understood from the neurobiological perspective. When Turing tackled the topic, he simply demonstrated that intelligence essentially boils down to performance when it can be concretely defined. In other words, if x produces y, and if a human would produce y in a manner that we, as humans, would deem intelligent, then x is intelligent (thus, the trick lies in constructing a transitive argument for comparison, etc., which is fair enough for programmers or pure logicians attempting to create some form of computing machine). Turing was very candid in setting limits to the thought experiment. I believe that intelligence pertains to a certain type of performance that necessitates specific properties at the causal level.

[I] If S produces x through I, where I has causal capacity such that x is not produced by chance and x achieve a solution for a given problem, then S is intelligent.

Alessandro Canfora scrive che in un quadro di Van Gogh la rosa sarebbe rozza solamente per via dei petali dorati, in arrivo dalla pressione delle…

Abstract

‘Time is said in many ways’, to paraphrase Aristotle. In this essay, time is comprehended in four distinct yet parallel ways: subjective time, event time, conventional time, and landscape time. Subjective time measures the interval between two subjective experiences recorded by memory. Event time represents the order of events involved in a process. Conventional time is the measurement of a given physical interval registered by a clock and intersubjectively assumed as common. Landscape time refers to the current disposition of all changing facts in the universe. These four types of time are independent and autonomous from one another, as the essay will demonstrate. Although distinct, these time types can be related, collectively contributing to our understanding of the concept of time and how we use the term in language. The conclusion supports a pluralistic view of time, where time is partitioned into four categories, each explaining a distinct portion of reality.

Introduction – Time in the History of Philosophy

Time was not a major concern of the Greek-Roman philosophical tradition. From one side, time was conceived as the form of the appearances, that is of what it does not exist. Parmenides, essentially, banned time from his ontology, as the only things that exist is ‘the being,’ which was to be intended as eternal, meaning a-temporal, an object that does not change, hence does not exist in time.[1] Any subsequent metaphysical approach which endorsed implicitly or explicitly any form of Parmenidean ontology (something that does exist in its perfection because it never changes) is, in a way or another, banning time in a very fundamental sense.[2] Both Plato and Aristotle essentially (here intended ‘literally,’ i.e. in their understanding of what ‘really exists’) endorsed Parmenides’ vision. For some interesting reasons, today this notion is called ‘Platonic,’ but the conception of a perfect unchanging being independent from how things look like in and through time is, in fact, originated by Parmenides.

Matteo Corradini fantastica su un serpente… “viaggiatore”. Esso avrà la pelle bianca, ma con un fiocco celeste alla base della testa. Nessuno è abituato a…

Al fine di rivelare i fondamenti della società occidentale moderna, sviscerandone le basi di pensiero per comprenderne a pieno l’essenza, è buona norma far poggiare i propri sforzi di studio sui grandi nomi della trattatistica filosofica medievale. Una prospettiva compendiale del settore della medievalistica, puramente filosofica, richiede di concentrare le principali teorizzazioni di pensatori diversi, anche piuttosto distanti nel tempo e nello spazio, al fine di rivelare una soggiacente base comune concorrente alla formazione, in diacronia, del pensiero occidentale.

Abstract: La scrittura filosofica di Nietzsche affascina e incanta con virtuosismi e abilità retoriche rocambolesche, colpi di scena e immagini grandiose. Il lettore viene immerso nell’aurea tragica e perentoria di una dialettica negatrice che fa trasalire per la sua persuasività nella critica di tutti i valori fondamentali della civiltà occidentale. Ma cosa ci vuole dire veramente? Contro cosa si scaglia il filosofo con tanta irruenza?

Per Aldo Carotenuto, il fantasma rispetto a noi diventa fenomenologicamente una “presenza che arretra di continuo”. Quello arriva da un “altro mondo”, ma subito vi…

Nota metodologica circa le problematiche riguardo la tradizione manoscritta del madrigale petrarchesco RVF 121 per mano di messer Pietro Bembo nel ms. Vat. Lat. 3197.

Avvertenza: Il presente lavoro, di ecdotica e analisi comparata e in compendio del madrigale RVF 121 nell’insieme delle testimonianze, manoscritte e a stampa, parte da un’operazione paleografica[1] del componimento sulla base di manoscritti rilevanti delle varie fasi della gestazione del Canzoniere.[2] In fase paleografica si è tentato di rimanere quanto più fedeli possibile a quanto attestato sul manoscritto di partenza. Non avendo tuttavia un intento di edizione diplomatica nel presente lavoro, quanto più interpretativa, le trascrizioni paleografiche di seguito presentate hanno subito emendazione rispetto i seguenti fenomeni: il contoide fricativo labiodentale sonoro /v/, la cui grafia è resa con quella del vocoide posteriore alto /u/, è emendato alla grafia moderna [v]; il contoide affricato dentale /ts/ o /ds/, la cui grafia è resa con quella del contoide fricativo palatale sordo /ç/, è emendato alla grafia moderna [z]; qualsivoglia grafema che nel manoscritto sia sottinteso mediante l’impiego grafico di un titulus è reso graficamente tra parentesi tonde; la punteggiatura, qualora non si sia fatto riferimento a un’edizione interpretativa, è disposta dall’autore dell’articolo sulla base delle scelte effettuate da Gianfranco Contini (1964).

Recensione d’estetica per l’esploratore Daniele Castiglioni, in occasione del Festival “20 di Siberia”: 2003-2023, da lui organizzato in Ottobre a Tradate (VA)

DANIELE CASTIGLIONI ED IL VECCHIO CANALE (FRA I FIUMI OB ED ENISEJ)

Daniele Castiglioni ha percorso a remi il vecchio canale che congiungeva (con l’aiuto d’un affluente naturale) i fiumi Ob ed Enisej. Alla fine egli compirà una vera performance, contro le difficoltà del momento. Infatti d’estate le acque possono calare di molto, le zanzare colpiscono improvvisamente a sciami, i tronchi abbandonati a se stessi occludono le strettoie, i remi un po’ alla volta si logorano ecc… Naturalmente, c’è anche la difficoltà di trovare un punto di ristoro, fra i piccoli paesi lontani per centinaia di chilometri.

(courtesy to Paolo Meneghetti)